The quest for cleaner air would at first glance seem to have aims that are unarguably good for all. But London’s recent experience shows that such schemes are not always popular. Christopher Court-Dobson reports from a political front line and asks what other cities can learn from the experience

Illustration: Scott Garrett

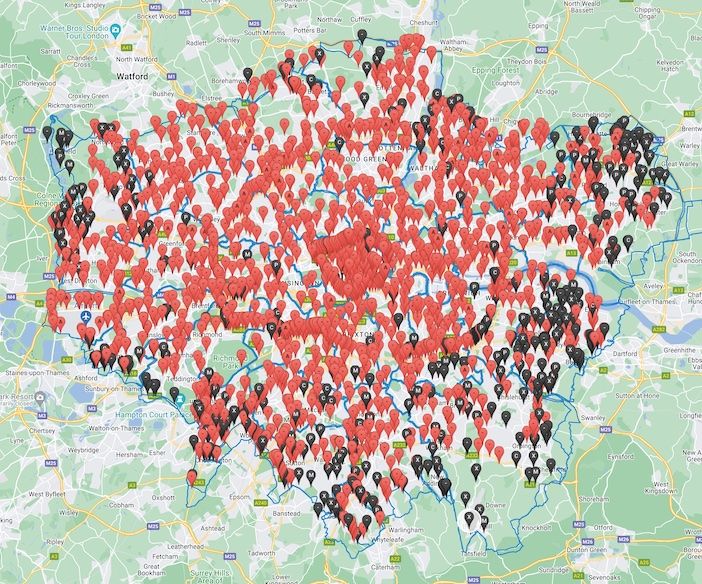

London’s Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) was first introduced in April 2019 by London Mayor, Sadiq Khan to tackle declining air quality, and operated within the same central area as the city’s Congestion Charge. In 2021 it was extended for the first time to cover a wider area within the city’s North and South Circular roads. Most recently, and most controversially, in July 2023 it was extended again to include all London boroughs.

At 380km² London’s ULEZ is the world’s largest clean air zone. It requires drivers of highly-polluting vehicles to pay a £12.50 per day charge for driving in the zone. While its aim of creating cleaner air seems like an unambiguous benefit for all, its expansion has come at the cost of an intense political backlash, with protesters saying it unfairly penalizes the poorest.

“There are people dying because of air pollution. We have to put that right. Sadiq Khan doesn’t control airports, or construction, only roads. That’s why he went for ULEZ”

Sarah Green, Green Party candidate for Uxbridge and South Ruislip, London

With low emission zones an increasingly common traffic management strategy for city authorities around the world, charged with reducing pollution and carbon emissions, what political and PR lessons can the international traffic management community learn from London’s ULEZ showdown?

The setting

Uxbridge, a borderland between London’s center and the English countryside, where suburbs turn to golf courses, canals, and finally, fields. Main street is diverse, working class. But also you’ll find country homes where celebrities go to retire.

The eclectic constituency of Uxbridge and South Ruislip was the seat of former Prime Minister Boris Johnson, and with his scandal-begotten retirement came last July’s by-election – one that the ruling Conservatives expected to lose. Their candidate Steve Tuckwell snatched a razor-fine 500 vote majority when he campaigned heavily on a protest-backed anti-ULEZ platform.

The stage

I’m at a busy noodle bar on Uxbridge high street, sat across the table from Sarah Green, the aptly named Green Party candidate who took third place – a good result for the small environmentalist party and her eyes shine with pride.

“ULEZ was weaponized, and used as a hate weapon against Sadiq Khan, which is unhelpful. We don’t need hate in politics,” she says.“There are people dying because of air pollution. We have to put that right. Sadiq

Khan doesn’t control airports, or construction, only roads. That’s why he went for ULEZ.”

Khan is a conviction politician, a savvy political bullfighter who doesn’t compromise on principle. But that’s not how the protesters see him. He’s been on the back foot recently, and ULEZ is set to be a thorny subject in next year’s mayoral race. “We had great coverage, but there were always leading questions from the media about ULEZ. They set the agenda,” says Green.

Behind the curtain

In the weeks prior to the by-election, a storm was brewing online. Not only had the protesters been hard at work, but it was later revealed in an independent report by Valent Projects that a fortune in dark money, an estimated £168,000, had been poured into fake accounts and digital manipulation.

When the dust settled, commentators framed it as Labour (the left-leaning main opposition party to the right-wing Conservatives in the UK) losing a seat they would have won had it not been for Khan’s ULEZ policy. But with so little in it, it’s hard to say for certain.

“It was presented as a loss for Labour. But I think that was a false narrative,” says Green. Whether ULEZ is to blame is complicated – but in politics the optics are important, and the image is that it is Labour’s Achilles’ heal.

But on the ground, Labour’s candidate, Danny Beales actually reversed his position and campaigned against expansion, but unlike Tuckwell, his stance did not carry over to voters.

Traffic management professionals and officials supporting clean air policies should be concerned. It’s often admitted that public communication is poor. In the hustings, arguments against ULEZ were many, and loud. But the arguments for it, and road user charging (RUC) more broadly, were absent.

In inner London, ULEZ expansion is overwhelmingly supported, with 62% in favor and 26% opposed. But in the outer boroughs it’s a different picture, with 51% opposing and 38% in support*. Such figures are, of course, hotly disputed.

In Uxbridge city culture, focused on public transit and smoked out by exhaust, meets the countryside, where the car is still indispensable. With further fuel on the fire provided by an inflation crises, rising inequality and an adversarial political landscape which sees the voices of the working class disregarded.

Front row

I’m at a lively ULEZ protest at Marble Arch in the West End and a man in a dinosaur costume has just lumbered by. Vans from the convoy are emblazoned with posters. One depicts Sadiq Khan as a rat, others read “No ULEZ no Pay-Per-Mile!” Some protesters sport T-shirts celebrating the infamous ‘blade runners’, who don masks at night to sabotage ULEZ cameras and have acquired a certain robin hood status within the outer boroughs. “I’m a bit old for climbing up ladders and hitting cameras. I don’t condone vandalism, never have done, but this is retaliation,” says Kate, a retiree who worked in accountancy.

When asked about her motivations, she says, “Businesses are going bust. People are having to leave their jobs. Nurses on a night shift have to pay double – £25 – if they can’t afford a new car, which on a nurse’s pay, I imagine is impossible.” The £25 is calculated as the charge runs midnight-to-midnight night, so shift workers are hit twice.

Reform (a Brexit Party spinoff) has sent its mayoral candidate, Howard Cox, another politician hoping to score a few votes on the back of ULEZ. “We all want clean air, we all want to have sensible environmental plans, but you don’t do it by hitting people in the pocket,” he says.

“I’m not opposed to the end game. I’m opposed to the implementation, because it’s affecting the poorest, most vulnerable people in our society”

Leo Phaure, ULEZ protest organizer

Clean air comes up a lot. In Uxbridge, one of the major gripes is that a sizeable proportion of emissions don’t come from residents. The 8-10 lane M25 ringroad can be heard constantly, bringing with it air pollution. Planes from Heathrow fly overhead, and construction of High-Speed Rail 2 (HS2) comes with a daily convoy of ULEZ-exempt trucks.

Leo Phaure, protest organizer and independent candidate in the by-election, is fed up with being stereotyped. “I’ve phoned LBC Radio, made my points. As soon as I put the phone down, they talk about right-wing climate change denial. I haven’t said anything about that.” Phaure was a solid Labour voter, but not anymore. He’s not interested in the latest fashionable cause, it’s about everyday economic struggles of the poor. But somewhat unexpectedly, he’s open to the idea RUC and ULEZ broadly. If done in a just way.

“I’m not opposed to the end game. I’m opposed to the implementation, because it’s affecting the poorest, most vulnerable people in our society,,” he says.

This might offer hope of a compromise. Many protesters have accepted the ULEZ expansion is irreversible. At this point it is a struggle for recognition, for their economic hardship to be taken seriously. This could be seen as an opportunity for city authorities rather than a threat.

“These policies don’t impact rich people at all. These are people who have already got their top-range EVs, but they’d also pay £12.50 without a blink of an eye,” says Phaure.

The reviews are in

A spokesperson at City Hall who preferred to remain anonymous, said the Mayor is listening to the valid concerns about ULEZ. But its position is that the negative impacts of ULEZ have been exaggerated for political purposes, highlighting generous grace periods and scrappage payments of up to £2,000 for cars and motorbikes, and £9,500 for vans: “Nine out of 10 cars in outer London are compliant and won’t have to pay a penny. For the small minority that do, help is available including thousands of pounds for low income Londoners, disabled Londoners, charities and small businesses.”

A key argument against ULEZ is that there is no sliding scale based on ability to pay – it’s £12.50 whether you’re a millionaire, or a struggling mum of three trying to get to work. This could be a wake-up call for policymakers who depend on increased public acceptance. To effectively change behavior the charge must represent a significant disincentive. But a flat rate hits the poorest hardest, often key workers who provide urban centers with their most vital of services. Meanwhile, wealth can buy the privilege of opting out – those who can most afford a less polluting vehicle are the least incentivized.

Dynamic tolling is incredibly versatile, and it could be tailored to provide a similar incentive to poor and rich alike, or even a progressive approach that places a higher burden on the wealthy.

Even with the fairest of policies, the benefits can be obscured in a world of sinister and sophisticated misinformation. The traffic management world will need to get much more serious about public communication, and a socioeconomically fair approach, or backlashes could only increase.

This article is edited from a longer version published in the March 2024 edition of TTi magazine