More e-scooters and bicycles on our streets mean lower carbon emissions and better last-mile connections, but with them come new traffic management and safety challenges, as David Smith discovers

Micromobility is in the middle of a massive boom in popularity, with e-scooters and rental bicycles becoming ubiquitous in cities worldwide. These new forms of transportation are often incentivized by governments and embraced by citizens, but nevertheless need careful management as they compete for road space with traditional modes, and add to the growing ranks of vulnerable road users (VRUs)

Over half of road fatalities worldwide are among VRUs (basically any road user not protected inside a metal box, which includes pedestrians). Figures from the UK’s Department for Transport (DfT) released last year show car occupants account for 44% of road fatalities, whereas for VRUs it is 50%. When calculated in terms of distance, there was a gulf, however. There were two car deaths per billion passenger miles, compared with 113 deaths for motorcyclists, and 26 apiece for pedestrians and cyclists.

Dash cams and head cams

Strategies for improving safety range from using high-tech artificial intelligence to optimize infrastructure, to more traditional policies like lower speed limits in urban areas. Some campaigners advocate mandatory dash-cams and intelligent speed assistance (ISA) systems to control drivers’ behavior. Meanwhile, cyclists are increasingly handing video footage of bad driving over to the police.

Dutch YouTuber Mike van Erp, better known as CyclingMikey, sees it as his civic duty to report dangerous driving and has handed videos of 1,100 bad drivers to London police since setting up his YouTube site in 2006. About 80% have been prosecuted, including celebrities like the ex-boxer Chris Eubank and the film director Guy Ritchie, who was banned from driving.

Van Erp posts his videos to YouTube after court proceedings are completed. It’s a controversial strategy with some newspapers labeling him a vigilante, but the police are strongly supportive, and van Erp argues that prosecution is the only way to convince some dangerous drivers to change their behavior.

“In my experience, almost no driver will change their law-breaking behaviors if I ask them to. To them I’m just an ‘oik on a bike’,” he says. “A few will change after a police officer gives them words of advice, but most revert to doing whatever they did wrong. I believe that drivers need to be prosecuted if we are to have much chance of altering their behavior.”

Van Erp quotes the founder of the London’s Metropolitan Police Force, Sir Robert Peel, in support of his strategy of encouraging “hundreds of eyes” to monitor the roads: “The police are the public and the public are the police; the police being only members of the public who are paid to give full time attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen in the interests of community welfare and existence.”

Personal cameras can also be installed in cars, and this is a safety provision favored by Dr Robert Davis, the chairman of the campaign group, the Road Danger Reduction Forum (RDRF), whose members are professionals in local government and traffic engineers. “If there’s one thing that would make roads safer, it’s mandatory dashcams,” he says “They’re entirely justified because people have been given this fantastically destructive power, but law-breaking is commonplace. Around 25% of drivers already have dashcams for insurance purposes as they provide evidence if something goes wrong. If all cars had them, police could look at the evidence and find out who is at fault.”

Do 20mph limits work?

The UK’s Road Safety Foundation (RSF), which carries out research on road safety, advocates for 20mph urban speed limits as the most critical solution. There is plenty of data in support of the speed reductions. For example, Transport for London’s recent analysis showed a 20mph speed limit on key London roads has led to a 25% reduction in collisions and serious injuries. A study of Spanish urban roads following a speed reduction to 30km/h (18.6 mph) in 2019 showed the same 25% fall in fatalities, amounting to 97 fewer deaths for VRUs.

“There are survivability curves showing the risk of being fatally injured rockets upwards beyond 20mph. The upshot is that under the safe system, we should be either managing vehicle speeds under 20mph where people are walking and cycling, or providing segregated facilities to enable them to walk and cycle away from danger,” says Dr Suzy Charman, executive director of the RSF.

Rod King, campaign director for the 20’s Plenty for Us group, says a lot of progress has been made in making 20mph zones more common. He said 18 million English people lived in areas with 20mph limits, including in the 14 largest urban areas.

Complete English counties, such as Lancashire and Cornwall, have introduced 20mph as a default in urban centers. Meanwhile, Scotland is looking to set 20mph as it’s norm in towns by 2025 and Wales will make it mandatory within its towns and cities on September 17 of this year. In many EU countries 30km/h (18.6mp/h) has been mandated in busy urban areas.

King argues that mandating 20mph is the most effective and cost-effective strategy. “It’s not a silver bullet, but it’s the best thing you can do that is population wide,” he says. “Most approaches to road safety are site-specific. Planners notice there are lots of crashes at a junction so they redevelop it. It’s concrete-led and suffers from the law of diminishing returns. You’ve got to put more and more concrete down to solve those issues. It’s like the difference between public health and surgery. If someone’s got a problem, you may have to fix it with surgery, but you can’t fix the overall public health of the nation by surgery.”

King also says there is evidence that site-specific calming measures can have some negative impacts. “They remind drivers they should revert to normal once they’re beyond the site,” he says. “When there is physical calming outside schools, drivers often speed up as soon as they’re beyond it. But children need to be safe all along their journey to school. That’s why we advocate population wide changes to speed limits.”

And introducing 20mph speed limits is far more cost-effective than re-engineering infrastructure. “You can put speed bumps down on a street, and it will affect 250 people,” he says. “It slows traffic down by 10mph. But for the same cost, you can put a 20mph limit across a whole community and reach several thousand people.”

Using AI to manage e-scooter taffic

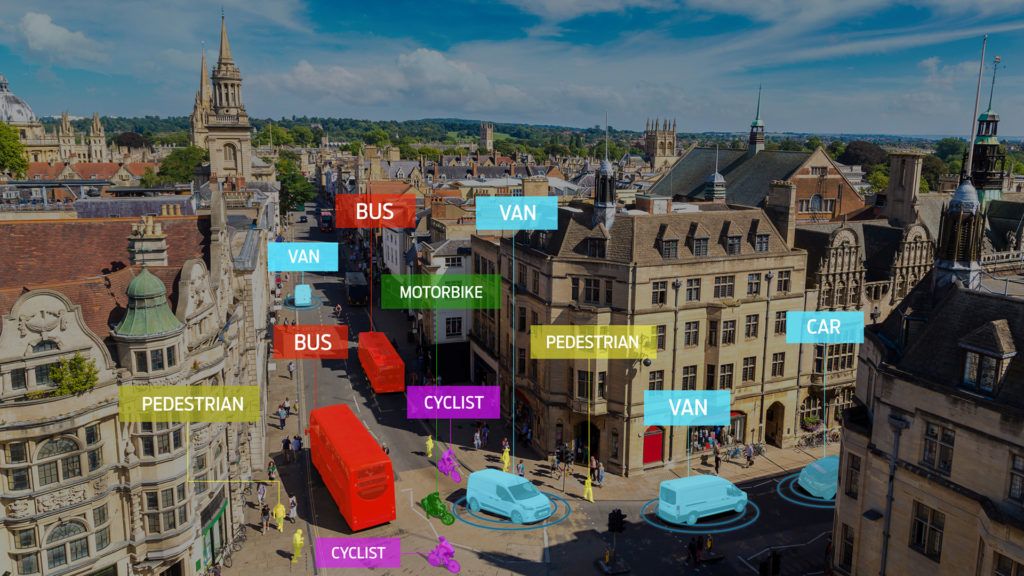

Leeds City Council has introduced 20mph into busy residential areas, but it is also turning its attention to managing micromobility more effectively by using AI detection from VivaCity. Unlike older rival systems the company’s Smart Signal Control: AI for Detection is able to differentiate between every road user. So, it can tell the difference between a pedestrian an e-scooter rider, a cyclist and a motorcyclist – and also between a car, a van, a truck and a bus. It does this using an AI engine connected in the Leeds pilot to more than 180 video-based sensors across 25 sites in the city.

By managing micromobility properly it’s possible not only to improve traffic flows for all road users, but also to encourage more citizens to use active travel solutions by prioritizing them at intersections and improving their safety.

The VivaCity sensors can be optimized for active travel by detecting bikes, or e-scooters, approaching a crossing from up to 70 meters away and providing a green signal for their arrival. It can then feed its data into existing urban traffic control (UTC).

“Traditional ways of controlling signals are focused on optimizing for chunks of metal going through junctions. But we’re in a world where we really care about active travel,” says Mark Nicholson, CEO, and cofounder of VivaCity. “Traditional signals don’t allow you to adapt for sustainable modes. The push buttons for pedestrians are pretty crude, for example. Everyone is stopped at a red light when the pedestrian has gone.

“Some systems provide advanced greens for cyclists but when there are no cyclists it’s frustrating for drivers. Or they sometimes override the entire system for a late bus. But it lacks the nuance to balance all these different modes. We’re feeding directly into an algorithm Leeds has created. Leeds is then using our data to manage its signals for multiple modes.”

The VivaCity video-based sensors also provide anonymized data about how fast road users are going. It’s not an enforcement solution, but it can be useful in analyzing the effectiveness of 20mph speed limits. They also provide data about near misses between vehicles and VRUs by identifying the 3D orientation of objects in the video and calculating the precise distance between them.

“We’re helping authorities to understand data more precisely, so rather than redesigning a junction because of one accident we can show the long tail of near misses to provide a much broader statistical basis,” says Nicholson. “It might mean they want to put in traffic calming measures, or signs to alert drivers to the dangers of passing cyclists. It might mean variable message signs at junctions, or new signal phase and timing. Do we want to put in an advanced cycles’ stop zone? Do we want to allow a filtered right turn? It gives the ability to make infrastructure decisions based on real safety data, rather than using gut feeling, which tends to happen today.”

While instinct can never be discounted as a sensible fallback in an emergency it’s clear that traffic managers now have many more tools at their disposal to help them steer the direction of the micromobility boom. And they will need all of them to ensure active travel becomes a safe, effective and sustainable mobility solution for the cities of the future.

This feature was first published in the May 2023 edition of TTi magazine