Increasing disquiet about the seeming inevitability of deaths on US roads, which have by far the poorest safety record of the G7 nations, is leading to a change in attitudes towards automated enforcement on highways, which is still not legally allowed in most states. Jack Roper and Tom Stone find out more as they investigate a groundbreaking pilot in Connecticut

Connecticut’s new automated speed enforcement pilot went live in Norwalk and East Hartford. Connecticut joins Pennsylvania and Maryland in deploying the previously unlawful technology to protect its employees and contractors in roadway work zones. Connecticut is known as The Land of Steady Habits – and an assiduous attitude proved useful as obtaining legislative approval for the Know the Zone Speed Safety Camera Program was a multi-year endeavor.

‘”In 2019, we began lobbying for special legislation permitting speed cameras in work zones,” says Connecticut Department of Transportation (CTDOT) communications manager, Josh Morgan. “The wheels of government move slowly. It took time to identify a vendor, issue a proposal and perform our due diligence. Our elected officials passed legislation, signed into law by our governor, allowing us to implement the pilot program in 2023.”

117 The number of workers killed in crashes in work zones in the US in 2020

CTDOT’s case was compelling. In 2020, 774 fatal crashes in US roadway work zones resulted in 857 deaths, with 117 workers amongst those killed. Connecticut saw 385 road deaths last year, the most in three decades, with reckless and impaired driving increasingly prevalent. In one work zone, CTDOT speed sensor monitors revealed that 60% of drivers exceeded the 55mph limit, which equates to tens of thousands of speeding vehicles each day.

“We have 1,300 employees out doing pothole work, or fixing metal guide rails,” says Morgan. “Following our snow season, they’re out there picking litter. Drivers in Connecticut throw junk out of their windows all winter long and that stuff collects on the highways. Those are some of the most dangerous work zones.”

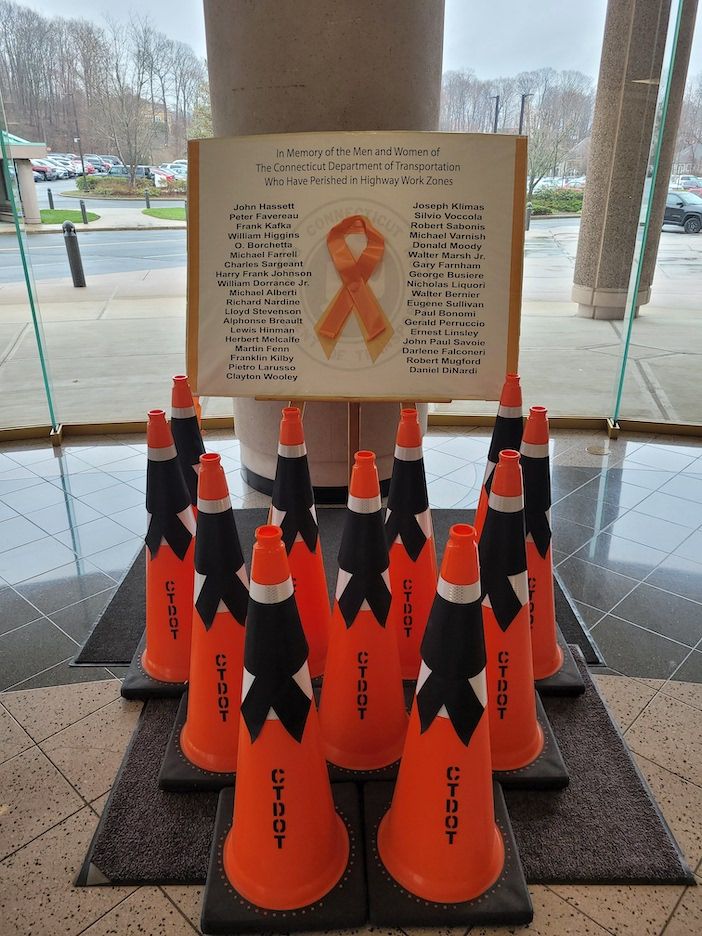

Contractors on major projects tend to install concrete Jersey barriers offering a good level of protection. But CTDOT roadside crews have only orange cones to protect them from vehicles flying past at 90mph as little as 5ft away.

“We have a memorial in our lobby with orange cones and black ribbons for almost 40 CTDOT workers killed in work zones,” says Morgan “Just this week, a vehicle crashed through a work zone, killing the driver. We just want our men and women to finish their shifts and arrive home safely.”

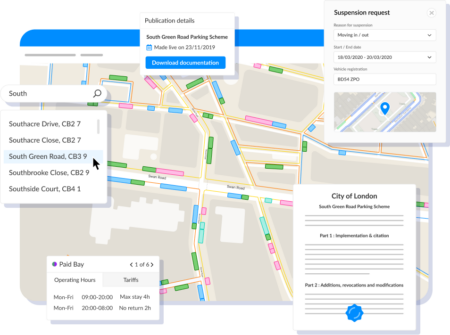

How automated enforcement works in Connecticut

The system consists of six Jeep Grand Cherokee SUVs equipped for automated enforcement. Trunk-housed radar technology detects any vehicle exceeding the posted speed limit by more than 15mph, then roof-mounted cameras capture its front and rear license plates. The legislation permits CTDOT to deploy three of these unmanned systems in work zones across the state at any one time.

“It’s an incredibly mobile system,” says Morgan. “Signage 500ft then 200ft ahead alerts motorists to its presence. If you’re still speeding, it grabs your license plate and sends a citation in the mail. We’re confident this will improve safety. We know the speeds in our work zones and data from other states shows how effective automated enforcement has been.”

12% The year-on-year increase in road fatalities on rural interstates in 2021 (NHTSA)

Connecticut’s provider, Verra Mobility, operates 300 safety programs worldwide and supports US partners with speed and red-light cameras as well as systems to improve transit efficiency. Verra presents automated enforcement as a no-lose proposition which pays for itself and saves lives.

“We take care of the upfront investment and operate the whole program for DOTs,” says Verra Mobility Executive VP for government solutions, Jon Baldwin. “We identify sites, install cameras, connect the power, connect to 5G backhaul and start policing as quickly as possible. Our back-office processes events and sends citations to police departments for validation. We maintain the cameras to ensure uptime above a service-level agreement. We provide court integrations when people want to contest their tickets.”

While CTDOT identifies locations for mobile SUV units, it is not an enforcement agency. Verra operates the technology and citations are verified by Connecticut State Police. Verra issues an evidence package for each offence and well-calibrated equipment precludes citations being successfully contested in court.

“A managed maintenance program will regularly verify that radars are within calibration and cameras are working as intended,” says Baldwin. “Our evidence package includes a video of your car, your radar speed and a zoomed-in license-plate image, so your car was definitely exhibiting the behavior the citation relates to.”

Careful deployment builds public confidence

Connecticut’s self-proclaimed ‘steady habits’ were evident in CTDOT’s conscientious due diligence prior to deployment of its enforcement solution. Enabling legislation was carefully crafted to safeguard privacy and address concerns raised by the American Civil Liberties Union that automated systems could disproportionately target underserved communities.

“In the 1950s, our interstate system bulldozed through previously thriving communities of color,” says Morgan (see Righting Wrongs, page 32). “We didn’t want to repeat wrongs of the past. The legislation requires us to notice camera locations 24 hours in advance. It will be across Connecticut, not just in cities, which are typically more diverse with lower median incomes.”

In a surveillance-averse state, privacy concerns focused on how information could be shared with law enforcement. Consequently, while Connecticut State Police may process citations, they cannot access camera footage, even to track known criminals. The system is designed only to capture front and rear license plates of speeding vehicles.

“We don’t photograph drivers,” says Morgan. “People sometimes say: But it wasn’t me driving! It was my son, or my…buddy! Well, that’s too bad. We send citations to registered owners, not drivers, to alleviate concerns about taking your picture.”

“We don’t have any personal information. If you break the law, we’ll capture your license plates but blur out any image inside the car. We only attach personal information when we do the motor vehicle department look-up. If cars are minding their own business within the laws, we don’t capture any information.”

Safety not revenue

CTDOT’s pilot is supported by a public outreach campaign across social media and roadside billboards. The focus is on saving lives, rather generating revenue. It issues only a warning for a first citation, then fines of $75 and $150 for second and third offenses respectively – compared to $600 fines for distracted driving in Connecticut.

CTDOT’s pilot is supported by a public outreach campaign across social media and roadside billboards. The focus is on saving lives, rather generating revenue. It issues only a warning for a first citation, then fines of $75 and $150 for second and third offenses respectively – compared to $600 fines for distracted driving in Connecticut.

“This isn’t a ‘gotcha’ campaign,” says Morgan. “The fines are minimal relative to the dangers involved. Neither is this 24/7 enforcement, with cameras always available. The system will only be activated when people are actually out on the highway fixing our infrastructure.”

42,915 The annual road fatality total in the US in 2021, a 16-year high. In 2014 figures were as low as 32,744 but have been climbing since

For its part, Verra typically provides a fixed-price service to government customers and is not incentivized to boost citations. It does see a proliferation of automated enforcement use-cases in the US where systems can protect the vulnerable. These include cameras to protect children boarding buses in school zones or, in current pilots, to enforce safe driving around bicycle lanes.

“We’re a safety partner to government,” says Baldwin. “We engage with any enforcement solution which could prevent accidents or reduce risky behaviors. As legislative support for distracted driving or seatbelt detection increases, we will offer those solutions. That applies to any imaginable safety application.”

Expanding enforcement

How far the law permits automated enforcement varies between countries and states. In the UK, Baldwin considers average speed enforcement schemes operated by Verra an effective tool for work zone safety. But on most US highways, automated enforcement is not permissible. Verra would support legislation to expand its use, but endeavors to depoliticize the discussion.

“We just spread the good word about how effective programs are in changing behavior and saving lives,” says Baldwin. “In New York City, our system has reduced red light running by 77%. City after city, we can pull the data down. We provide data to community outreach partners focused on improving safety, whether by automated enforcement or other tools. Last year, the US had over 40,000 roadway fatalities and there’s much more we can do.”

In Connecticut, there is already a bill before the General Assembly to expand the current program and allow speed and red-light cameras in selected areas of cities. CTDOT supports separate legislation to reduce the blood alcohol limit for drivers in the state. Morgan sees desire for wider implementation of automated safety gathering real momentum.

“We expect our data to demonstrate that this pilot has reduced dangerous driving by next year,” he says. “Then we’ll have a good case to expand automated enforcement to school zones or areas with high pedestrian or bicycle traffic. I think there’s strong support from the public and elected officials, because the number of fatalities is really unacceptable. We need to reverse that trend.”

Righting wrongs

Enforcement roll out is being done with social equality in mind – as new funding attempts to overcome the negative impacts of interstate construction

President Biden’s $1.2 trillion Bipartisan Infrastructure Law established the Reconnecting Communities Pilot (RCP), making available $1 billion in discretionary grants to address injustices created by the 48,756-mile US Interstate Highway System.

“Good transportation connects us to jobs, services and loved ones,” said Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, last year. “But sometimes America has gotten things wrong. Then, infrastructure can do the opposite, dividing or damaging communities.”

Interstates construction authorized in the Federal Aid Highways Act of 1956 often bulldozed through Black communities, destroying them or creating barriers to integration and prosperity. The American Civil Liberties Union states that roads sometimes followed boundaries used in the racial zoning that courts had begun to strike down.

“We can’t ignore the basic truth,” Buttigieg continued. “Some planners and politicians behind those projects built directly through the heart of vibrant, populated communities. Sometimes to reinforce segregation. Sometimes in a direct effort to replace or eliminate Black neighborhoods.”

In 1966, Claiborne Avenue in New Orleans, a once-thriving Black business district with oak-lined parkland, was eviscerated by a six-lane I-10 overpass. Now, Reconnecting Claiborne aims to remove divisive I-10 on- and off-ramps and create cultural amenities under the road.

“We have funding to make better choices,” said Buttigieg. “That might mean capping a highway and putting a park over it where kids can play, or introducing bus rapid transit connections between previously isolated neighborhoods.”

In securing bipartisan support for the Infrastructure Law, proposed RCP funding was reduced from $20 billion to $1 billion. Reconnecting Claiborne received a $500,000 RCP grant towards its estimated $94m cost.

Funds may not match the program’s ambition and it is not without its detractors. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis doesn’t understand how roads can be discriminatory and dismisses the endeavor as ‘woke’.

Nevertheless, it establishes racial equity as a dimension to consider in any US transportation project – including automated enforcement pilots.

“This is the first dedicated federal initiative to repair harm caused by infrastructure choices of the past,” said Buttigieg. “Roads and bridges are not divinely ordained. They are decisions – and we can make better decisions than what came before.”

Enforcement goes green

The transformative power of automated enforcement extends far beyond detection of speed or red-light infractions. It can be harnessed to change driver behavior in positive ways and make transportation work more efficiently. For example, enforcement of bus lanes can discourage drivers of unauthorized vehicles from using them, which helps public transit to run on time and in turn encourages more people to use it.

“Fewer people will use buses which run late,” says Verra Mobility’s Jon Baldwin. “We deploy technology to prevent people driving in bus lanes or parking at bus stops. They’re parking-type tickets, rather than criminal infractions. It significantly improves the efficiency of public transit and helps solve traffic congestion.”

This feature was first published in the May 2023 edition of TTi magazine