With AI and virtual reality at our fingertips, models of future traffic patterns are becoming more accurate than ever before – but obtaining and processing data is a huge challenge, as Jon Lawson finds out from experts in Europe and the USA

Transport modeling is big business, and it’s getting bigger. According to a report published in February 2024 by Kings Research the worldwide market will be worth US$7.83 billion by 2030.1

Unsurprisingly, underpinning the commercial market there are active research programs within government bodies and across academia.

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) has been a leader in developing traffic simulation models since the 1970s. In the 1990s, it packaged its work into a single traffic simulation model called Traffic Software Integrated System/Corridor Simulation, commonly known at TSIS/CORSIM.

It was the only viable traffic simulation model available at the time and became a catalyst that sparked the successful transfer of technology from government to the private sector.

Carl K Andersen is acting director of the FHWA’s Office of Safety and Operations Research and Development. He says: “Computing power has continued to grow – which makes the capability of traffic simulation modeling more powerful and complex. We can now increase the size and diversity of the road networks we analyze, introduce more elaborate origin/destination pairs and route choice algorithms, and analyze multimodal travel choices to provide a more complete picture of how the transportation network may be used.”

Operationally, these more powerful computing capabilities allow agencies to increase the complexity of software used by vehicles and traffic management centers.

Traditionally, traffic data sources were centralized and often obtained from publicly owned systems like loop detectors, traffic counts, and police reports. Today, data sources are abundant, including mobile phone data, infrastructure camera data, satellite data and connected vehicle data.

However, one problem with data from vehicles is that is OEMs are often protective of it, not willing to make it freely available for traffic modeling. This is an international problem.

Clas Rydergren, a professor of traffic informatics who specializes in transport modeling and analysis at Linköping University in Sweden says, “Connected vehicles can provide more information not only about your own vehicle, but also others. Where this data is collected by the car manufacturers, it would be great to have access to use it for simulations.”

In the US, Andersen is optimistic about future possibilities for open data: “The FHWA is working with academia, the private sector, and other government agencies to address challenges related to access, security and interoperability of new data sources.”

Quality control

Rydergren agrees with Andersen that data quality is one of the key drivers for improving digital models. He works closely with the Swedish Transport Administration and regularly discusses ways to improve forecasting.

“The driving force behind the requested improvements is often the sensor systems, and what this means for data quality,” says Rydergern. “These systems have traditionally been infrastructure-based, such as radar for motorway control, counting vehicles on streets and cameras in the more advanced systems.”

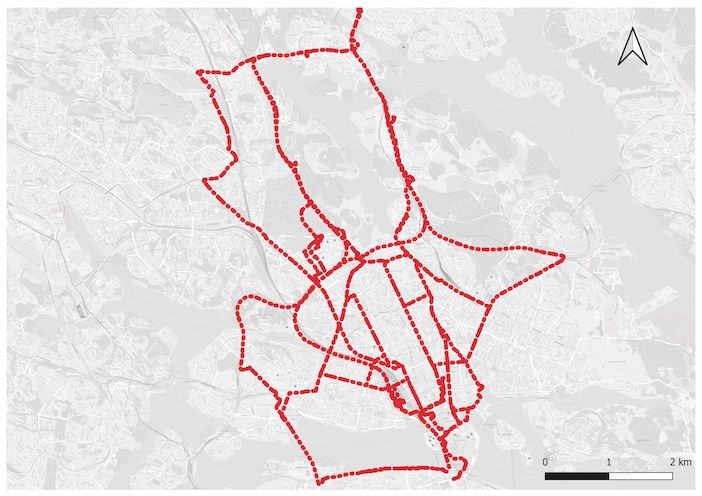

In the future road authorities around the world are looking to minimize the use of data collection hardware in their operations since it is expensive to maintain. Instead, as well as investigating the possibilities of collecting data from cars themselves, the potential of anonymized mobile phone data is being look into as a new resource for traffic modeling.

“Mobile phone manufacturers are important,” says Rydergern. “We are already working with them so they can give useful inputs to our models. It’s exciting, but we’re still uncertain about the quality but we know saome of the mobile phone companies are spending lots of time on this.

“Telia for example did good work during Covid looking at the mobility of Swedes, creating a commercial product that they could sell. Having the mobile operators give us a start and end points of trips may be complicated to measure, and this technology is in its early stages, but it does add a new dimension.”

AI evolution

Artificial intelligence has loomed large in the public consciousness recently, but applications of AI and machine learning in transportation have been developing for years.

In 2019 Delaware DOT published a report entitled Raising Awareness of Artificial Intelligence for Transportation Systems Management and Operations2, which looked at, among other things, AI for incident detection, ramp metering, traveler information and drones. It even touched on the use of natural language Q&A systems in chatbots.

AI and machine learning can take the form of sophisticated static statistical models that represent complex dynamics, or learning systems that evolve with near-real time data.

“One area where AI could be really useful is in managing the collection of data from multiple sources. Machine learning could help in combining video data with sensor data from vehicles, for example”

Clas Rydergren, professor of traffic informatics, Linköping University, Sweden

A further example of its use is in the USDOT’s Intersection Safety Challenge3. Focused on improving safety for vulnerable road users, it is developing AI capabilities for traffic management and operations.

“The application of AI and machine learning may result in decision-support systems that help traffic management centers respond more proactively to traffic issues to improve safety and traffic operations,” says Anderson. “For instance, machine learning-based algorithms may inform dynamic speed limits based on weather, traffic or other conditions. It might enable earlier detection – even possibly prediction – of incidents to apply countermeasures or improve emergency response.”

Rydergren sees another possible application for this new technology: “One area where AI could be really useful is in managing the collection of data from multiple sources. Machine learning could help in combining video data with sensor data from vehicles for example. The technology is nearly there, but a lot of validation needs to be done.”

The future of modeling

The FHWA is interested in developing a connected and interoperable transportation. For example, via the USDOT’s Virtual Open Innovation Collaborative Environment for Safety (VOICES). This is a simulation platform that enables users from multiple locations to simulate and test together simultaneously in a secure environment.

The goal of VOICES is to identify and resolve conflicts between different road users earlier in the development process, thus improving safety for all road users.

“Since 2020, this has enabled FHWA to collaboratively test connected, automated and ITS applications with partners from government, industry and academia,” says Andersen. “This kind of co-simulation is unique because it enables organizations to protect their intellectual property while testing how existing or prototype systems interact with other simulated road users.”

In addition to this program, the FHWA has engaged with stakeholders to assist in the development of a connected and automated vehicle (CAV) analysis, modeling, and simulation (AMS) research. “It was clear from stakeholders that insights from automotive and technology providers will be a key to building better models of CAV behavior,” says Andersen.

As vehicle autonomy increases, the response has been the creation of a new tool: Cooperative Driving Automation Simulation (CDASim), which pulls connected infrastructure, cloud and vehicle capabilities into one simulation in order to study and prototype applications where the three can interact to improve safety and efficiency.

“Models [of human/AV interaction] will be provided as open-source software to the industry for potential updates to existing traffic-simulation products”

Carl K Andersen, acting director, Office of Safety and Operations Research and Development, FHWA

“At a broader, regional traffic level, we are working to characterize both how connected and automated vehicles themselves behave, as well as how surrounding human drivers respond,” says Andersen. “In recent years, FHWA has conducted multiple data collection projects in Chicago, Columbus, and Washington DC that will be used to characterize and then update the models of mixed human-driven and automated vehicle traffic flow. These models will be provided as open-source software to the industry for potential updates to existing traffic-simulation products.”

“An interesting part with automation is the intermediate stage – in other words what influence will advanced driver support systems have?” asks Rydergren. “We must consider the full spectrum from manually controlled cars right up to full autonomy. Even if the vehicles don’t fully drive themselves the vehicle behavior on the road will change over the next five years. Road manners will adapt to be more, or less, aggressive.”

Overall traffic modeling is an increasingly complex field, with richer data making full use of available computing power even as that increases. “Better computers will make the simulation process much faster,” says Rydergren. “Taking the national forecasting model as an example, to run a single simulation takes 24 hours. It’s too complicated to validate things such as sensitivity analysis with such a slow model, so more powerful computers will certainly help. On the other hand, all these new data sources will add complexity so the outcomes may be better, but the speed may still be slow.”

So, as far as traffic modeling in the future is concerned, despite the rapidly increasing rate of change, it may still hold true to the old that good things will come to those who wait.

1) www.kingsresearch.com/request-sample/traffic-simulation-systems-market-24

2) ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop19052/fhwahop19052.pdf

3) its.dot.gov/isc

This is an edited version of the full article which was first published in the March 2024 edition of TTi magazine