According to new research from the UK’s Transport Research Laboratory (TRL), human drivers do not yet know enough about autonomous vehicles (AVs) to take advantage of them.

The study, conducted by TRL as part of the UK government-backed GATEway (Greenwich Automated Transport Environment) driverless car project in Greenwich, investigated how human drivers might adapt their behavior in the presence of AVs. Results indicated that the majority of motorists did not change their driving behavior, and continued to make decisions about overtaking or pulling out into traffic based on gap size assessments and judgements of safety. This exploratory study will be followed by trials of automated passenger shuttles and automated urban deliveries later this year.

The trial, which took place in TRL’s DigiCar full mission, high fidelity driving simulator, sought to explore how human drivers will respond to automated vehicles in an urban environment. Participants completed a series of short simulator driving scenarios within a 3D virtual replica of the Greenwich Peninsula, developed by modelling and simulation specialists, Agility3. These scenarios included overtaking and junction driving tasks, with the recognizability and proportion of AVs in traffic varied to represent the transitional phase between a fully and partially automated vehicle fleet.

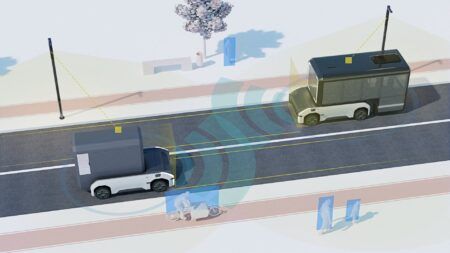

Overall findings suggest driver behavior would remain largely unchanged in the presence of AVs, however tentative evidence was found that some drivers may adapt their driving behavior as autonomous vehicles become more prevalent. For example, drivers were found to pull into smaller gaps between vehicles at junctions when there are more automated vehicles in the traffic, but drivers did not necessarily intercept AVs more readily than human driven vehicles.

Commenting on the results, Professor Nick Reed, academy director at TRL, explained, “What we have found suggests that people find it hard to recognize automated vehicles and/or don’t yet understand how automated vehicles behave. In terms of their driving behavior, they therefore treat them as they would any other vehicle. It is possible that this could change as exposure to autonomous vehicles increases, but more evidence is needed to substantiate this. A small number of participants did pull out into smaller gaps when there were more automated vehicles in the traffic. This could be due to an increase in confidence about pulling out in front of an automated vehicle, with some participants citing this as a reason. We would be interested in understanding why these drivers took this approach and how these behaviors evolve over time.”

Reed continued, “As automation becomes more prominent in vehicles, we are likely to see a mixed fleet of non-automated, partially automated, highly automated and (eventually) fully automated vehicles for many years to come. Through that transition period, human drivers and other road users will be encountering autonomous vehicles in increasing numbers. The way in which human driven and automated vehicles interact will have major impacts on traffic flow dynamics and road safety. Understanding how these vehicles will coexist as we move through this transition phase will be critical for infrastructure planning and road safety.”