The world’s most prestigious engineering accolade, the Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering (QEPrize) has been awarded to four engineers from the USA responsible for creating GPS, the first truly global, satellite-based positioning system.

Presented every two years, and coming with a £1m (US$1.28m) award, the QEPrize celebrates the global impact of engineering innovation on humanity. The 2019 winners are Dr Bradford Parkinson, Professor James Spilker Jr, Hugo Fruehauf and Richard Schwartz.

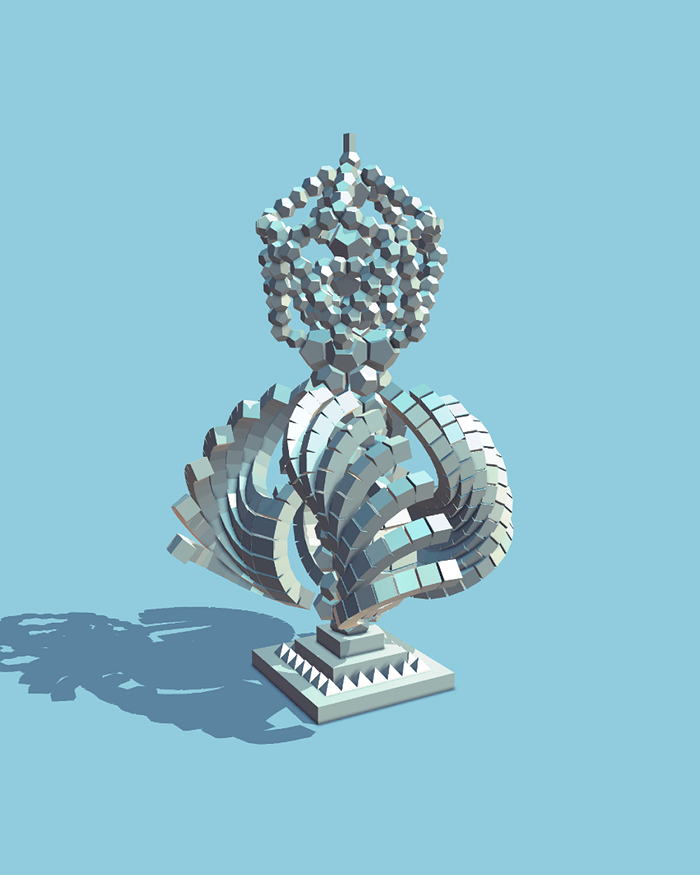

The winners will also receive an iconic trophy designed by the 2019 Create the Trophy competition winner, 16 year-old Jack Jiang from Hong Kong. A cornerstone of modern transportation systems, GPS represents a pioneering innovation which, for the first time, enabled free, immediate access to accurate position and timing information around the world. Today, an estimated four billion people around the world use GPS, and its applications cover most aspects of modern life.

The winners will also receive an iconic trophy designed by the 2019 Create the Trophy competition winner, 16 year-old Jack Jiang from Hong Kong. A cornerstone of modern transportation systems, GPS represents a pioneering innovation which, for the first time, enabled free, immediate access to accurate position and timing information around the world. Today, an estimated four billion people around the world use GPS, and its applications cover most aspects of modern life.

GPS uses a constellation of at least 24 orbiting satellites, ground stations and receiving devices. Each satellite broadcasts a radio signal containing its location and the time from an extremely accurate onboard atomic clock. GPS receivers need signals from at least four satellites to determine their position; they measure the time delay in each signal to calculate the distance to each satellite, then use that information to pinpoint the receiver’s location on earth.

The basic tracking required for GPS dates back to the start of the space race, when radio operators tracked Sputnik I on its groundbreaking flight in 1957. Sputnik’s radio signals appeared to drop in frequency as it passed overhead, a phenomenon known as the Doppler shift that allowed the satellite’s position to be determined.

The chief architect, Parkinson, directed the program and led the development, design and testing of its key components, insisting that GPS needed to be intuitive and inexpensive, making navigation accessible to billions.

To realize the project, he recruited Spilker to design the signal that the satellites broadcast, ensuring it is resistant to jamming, precise, and allows multiple satellites to use the same frequency without interference.

To realize the project, he recruited Spilker to design the signal that the satellites broadcast, ensuring it is resistant to jamming, precise, and allows multiple satellites to use the same frequency without interference.

Freuhauf, then chief engineer at Rockwell Industries, led the development of a miniaturized, radiation-hardened atomic clock that satellites use to transmit data to GPS receivers on earth. Schwartz, the program manager at Rockwell, was tasked with ensuring the satellites’ longevity. His design was resistant to the intense radiation from the upper Van Allen belt, and had a nine-year life span.

Asked whether the winners knew that GPS could change the world, Parkinson said, “Back in 1978, I made a few drawings that depicted GPS applications that I could personally foresee; they included an automobile navigation system, semi-automatic air traffic control and wide-area vehicle monitoring, and seem to be rather accurate 41 years later. That said, none of us could fathom the sheer breadth of GPS applications.”

Giving his future predictions for GPS, Schwartz commented, “It’s hard to imagine what young and creative engineers will come up with next. That said, in the not too distant future I think I will be able to step into a driverless car, tell the car where I’d like to go, and then sit back and enjoy the ride.”