What’s the next big thing in traffic enforcement? For a much-overlooked answer, take a trip to Kensington or Taipei. Bring your earplugs.

These two locations could not be more dissimilar, yet both have conducted successful trials of vehicle “noise cameras” to issue fines to loud cars and motorbikes, following years of mass complaints from sleepless residents.

Vehicle noise pollution is a global problem which takes many forms. Taipei suffers from “scooter waterfalls” – which must be seen to be believed – while Kensington is plagued by supercars. Rowdy car meetups in retail parks are a further problem – in fact they’re a global scene, one that has spawned its own social media superstars like AdamC and his 600k followers. A fear of speed cameras means that car culture is now just as much a celebration of noise as speed, and every police force and local government around the world groans under a weight of complaints about noisy car cruises.

In October 2021 Taiwan announced plans to spend $4m on a national network of noise enforcement cameras. Kensington has only 150k residents, yet its borough council spent a healthy £75k on a trial camera, which collected circa £5k per month over a three-month period. The politicians behind such schemes are pushing on an open door: over 85% of residents in Taipei and Kensington say they strongly approve of noise cameras. Plainly, voters prefer peaceful homes to loud exhausts. Other cities are trialling noise cameras too. If the rest of the world goes on to spend like Taiwan, the market for vehicle noise enforcement will easily exceed $1bn – a decent prize for any global ITS firm.

Compared to speed enforcement, noise enforcement schemes are straightforward. The cameras have been broadly self-financing in most locations, despite being barely out of prototype. Better yet, noise is unlike speed in that it is a civil offence, not a criminal one. This lowers the legal bar for prosecution, and in many cases can be pursued not only by police but by local councils too. Best of all, cash-strapped local governments may keep the penalty revenue from noise tickets. The town of Elkhart, Indiana has collected over $1.6m in noise fines from a population of just 52,000.

Vehicle noise is not confined to a few hotspots: it’s everywhere, not least because the authorities appear to have lost control of vehicle noise regulation. Loud cars really went mainstream in the late 1990s, when vehicle manufacturers expanded the production of their sports brands, such as Mercedes’ AMG. These firms used fierce lobbying and some Dieselgate-style tactics to neutralise noise rules. Even today, some sports car manufacturers enjoy noise exemptions from the EU on the basis of being a “low production-volume manufacturer.” Production volume may be low in any one year, but the numbers add up over time: there are now over 30,000 Porsche Boxsters on UK roads alone, to name just one model. Making matters worse, owners of noisy cars love to add illegal exhaust modifications, which are surprisingly tough for the police to prosecute, even if they are easy to hear.

The public has certainly spotted that roads are louder lately. In a 2020 survey conducted by Kantar in the UK, over 75% of respondents “overwhelmingly agree” that the Government should act to reduce traffic noise. A 2012 survey by the UK Government found that 60% of UK households suffer with exhaust noise daily.

Unfortunately, the outlook remains noisy. It will be several decades before silent EVs might make much difference – if ever. A growing band of rebel drivers seem to define themselves by a dislike of EVs and the green agenda. Most of the noisy cars on sale until 2030 will still be viable in 2050: noise cameras will write plenty of tickets before that date, and quite some time after. If anything, noise cameras and EVs seem to be creating each other.

Noise has a price. There is evidence to link transport noise to a startling range of medical conditions, including heart disease, strokes and impaired learning in childhood. Some of the harm is thought to stem from sleep disruption and the sustained release of stress hormones. In 2021 a Danish study linked transport noise to the risk of dementia. In a cruel irony, dementia patients may also develop a profound and distressing sensitivity to noise, as can children and adults with sensory-processing disorders such as autism. Sudden loud sounds can cause children with autism to bolt or hide and adults to withdraw from public life. Some cannot speak for themselves and suffer behind closed doors.

More widely, transport noise is experienced as a home intrusion, one that prompts voters to complain in huge numbers. New York City received a staggering 99,000 vehicle-related noise complaints in 2020 alone, following which the State of New York increased vehicle noise fines from $100 to $1000. The US Bureau of Transportation Statistics estimates there are 800,000 homes in America where the background noise never falls below 75 decibels – or the sound of a vacuum cleaner running 24/7. Imagine teaching a child to read in such a home. There is an established medical and political justification for noise enforcement.

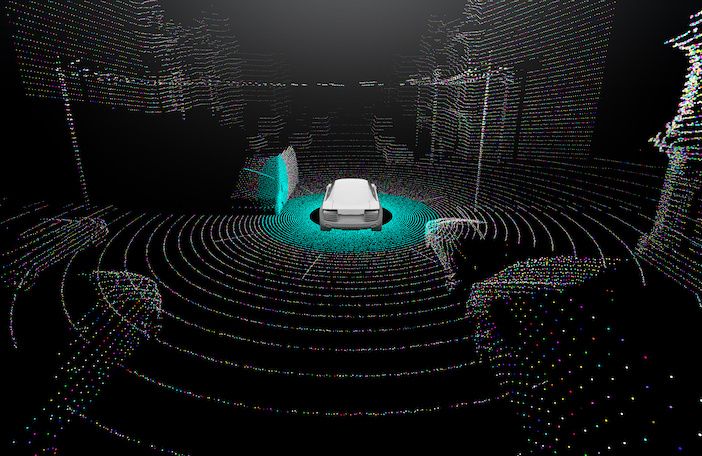

The bad news is that 1st-generation noise cameras are expensive – and often inaccurate, thanks to the limitations of audio microphones. A recent DoT report by Atkins Jacob revealed that its prototype noise camera needed a 10-second gap between vehicles – clearly unsuitable for busy roads. The good news is that even a patchy 1st-generation camera can have a deterrent effect, and that a 2nd generation of noise cameras is under development; these eschew traditional microphones and promise accurate measurement in heavy traffic.

It’s notable that noise camera manufacturers are all newcomers to the ITS industry. With no core business to worry about, they took a chance and established a new niche. Their early success ought to encourage more established ITS firms to join in.

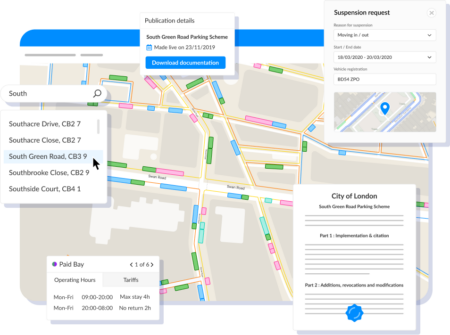

ITS firms should look ahead to a world in which traditional enforcement cameras can measure noise at little additional effort to speed enforcement – because that is next. General Noise Ltd, has patented the algorithmic basis for a radar/lidar traffic camera that can detect speed and noise violations all from one data signal. Thus a fixed or mobile speed enforcement set-up may soon be able to write tickets for noise too, for almost no marginal increase in technical overhead. That will help noise enforcement to become ubiquitous.

Noise enforcement suits the public because most of the planet lives close to a road. It suits the international political agenda, because noise is wasted carbon. It especially suits local politicians, as they are besieged with complaints and badly in need of revenue post-Covid – especially if that revenue can be raised from a small, visible and politically friendless group.

Of course, noise enforcement won’t suit lovers of loud cars and modified mopeds, but even the residents of Taipei and Kensington are OK with that. Taipei has one moped for every 2.7 people; Kensington can sound like it has more Ferraris than residents. When two utterly different transport cultures successfully prosecute and monetise noise, it’s surely a clue as what big ITS firms should build and sell next.

By Jason Dunne, co-founder of GeneralNoise.co.uk, a noise camera technology firm based in California and the UK.

By Jason Dunne, co-founder of GeneralNoise.co.uk, a noise camera technology firm based in California and the UK.

Photographs: Adobe Stock, Oscar Sutton/Unsplash, Pixabay